Basics of spine

The Anatomy of the Lower Spine

Our spine performs several functions which to some extent seem quite contradictory.

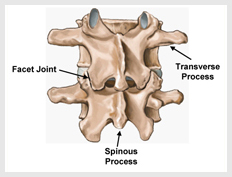

The spine supports us and keeps us upright, and must transmit large forces through our body, for example when we run or jump. In consequence the spine has to be strong and relatively rigid. But the spine is also a mobile structure. We need to be able to bend, lean and twist. These movements must be controlled to protect the delicate spinal cord, which runs within the spinal column in the spinal canal, and the nerves which emerge at each level. Meeting all these different requirements requires some complex structures and joints.

The building blocks of the spine are the individual bones called vertebrae. There are five in the lower back or lumbar spine, numbered from L1 at the top to L5 at the bottom. These are located above the pelvis. The central part of the pelvis, called the sacrum, is in fact part of the spine, formed from several vertebrae which have become joined together, or fused, into one solid bone. Below the sacrum are a few rudimentary vertebrae (the evolutionary hangover of our tail) which form the coccyx.

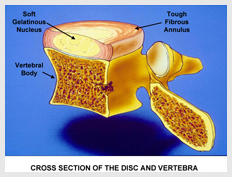

The main bulk of each vertebra is the cylindrical vertebral body. The intervertebral discs are found between the vertebral bodies. These discs act as a firm cushion or shock absorber but also allow some movement between the vertebrae. Contrary to popular myth, the discs cannot slip in and out of position since they are very firmly bonded to the vertebral bodies. The discs are named according to the vertebrae they lie between, so the disc between the 4th and 5th lumbar vertebrae is called the L4/5 disc, while that between the 5th vertebra and the sacrum is called the L5/S1 disc.

Disorders of the Lower Spine

Many of the problems that affect the lower back result from a wear and tear process called degenerative change. It is important to emphasise that these changes often occur as part of the natural ageing process that affects us all. In many cases they cause no symptoms at all, or no more than very mild occasional back ache or stiffness. Unfortunately, some individuals are affected more severely by these. This section looks at how these changes develop and the problems that may occur.

One of the first changes to affect the intervertebral disc is a gradual breakdown of the material which makes up the central nucleus. This may cause the disc to become a little soft and ‘wobbly’ much like a tyre which has had some of its air let out. This can lead to a sense of vulnerability in the back which is due to abnormal movement between the vertebrae. Somebody affected by this problem will lean or bend forwards slightly and their back will ‘go’ suddenly and very painfully. This is referred to as instability and forms the basis for some surgical procedures which aim to restore stability.

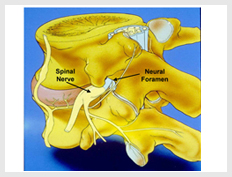

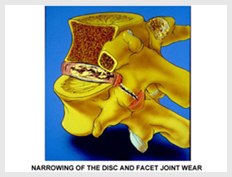

As the damage progresses the disc will gradually collapse, becoming narrower. The loads through the disc, normally spread out evenly, become ‘lumpy’ with painful areas of high stresses. The shock absorption capacity of the disc is reduced. The openings for the nerves leaving the spine, the neural foramen,

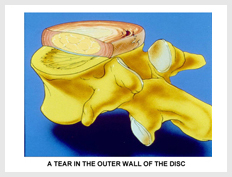

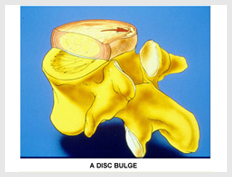

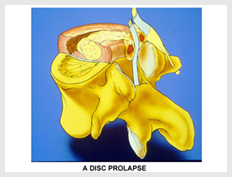

During the early stages of wear and tear affecting the intervertebral disc the outer wall of the disc, the annulus, may be weakened. Stress tends to be concentrated in the back corners of the disc, which shows more signs of wear and tear as a result. During bending movements pressure within the disc is concentrated at this spot.

There are various ways that degenerative changes can cause low back pain or pain spreading down one of the legs.

Discogenic Pain and Annular TearsDiscogenic pain arises from the disc itself. Areas of high stress within the disc can be uncomfortable, particularly with standing or sitting for long periods. The disc will also be vulnerable to jarring, for example causing pain when a step is missed. Inflammatory substances build up in the disc and can leak out through tears in the disc wall (annular tears) causing back pain and sometimes nerve pain as well. This is occasionally referred to as ‘chemical spill’. Annular tears can be seen on MRI scans and are by no means always symptomatic. However, it has been shown that very sensitive new nerve fibres can grow into these tears and cause pain.

InstabilityThe instability from softening of the disc may cause sudden painful episodes which may last days, weeks or longer. There will often be a sense of vulnerability with certain movements which, of course, will lead to functional limitations and a gradual stiffening of the back.

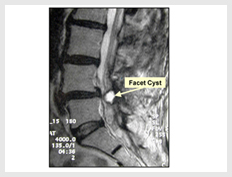

Facet Joint DiseaseAs with any other joint arthritic changes affecting the facet, joints can be painful. This may be helped by injections of anti-inflammatory steroid into the joint or by radiofrequency denervation of the affected joints. When joints are affected by arthritis they may enlarge. This enlargement is not really a problem in other joints, although it can be a little unsightly. In the spine this enlargement can encroach on the space available for the spinal nerves, a condition called spinal stenosis.

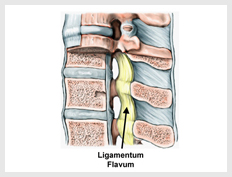

Spinal StenosisThis is a critical narrowing of the space available in the channel for the spinal cord and nerve roots which run down the spine. This channel is called the spinal canal, and the narrowing which occurs is usually due to a combination of bulging of the intervertebral disc, encroaching on the canal from the front, and overgrowth of the facet joints narrowing the canal from the sides and the back of the canal. With these changes, ligaments within the canal thicken and bulge, particularly when standing upright, adding to the problem.

Sometimes an individual may constitutionally have a rather narrow canal to start off with, leaving them prone to stenosis even with fairly modest degenerative changes. B ut in most people the changes tend to be quite advanced. Since these degenerative changes tend to progress with age, spinal stenosis is more common in older age groups. The commonest form of narrowing, central canal stenosis, affects the whole of the spinal canal, constricting all nerves at that level of the spine. This often causes a rather diffuse back ache which spreads into the buttocks. Standing or walking typically causes an aching heaviness and tiredness in the legs which, together with the back ache, steadily builds up to the point that the person may be unable to carry on walking and has to sit down. The distance they can walk is a useful indicator of the severity of the stenosis. Sitting down often brings on very rapid relief because this position bends the spine forwards, stretching out the ligaments which were buckling into the canal. After a few minutes of sitting, a person with spinal stenosis will generally be able to continue walking until their symptoms stop them again after a little while. Walking in a somewhat stooped posture, for example while pushing a shopping trolley, is often easier since this again stretches out the ligaments in the spinal canal. The patient with spinal stenosis often becomes stooped for this very reason. Aching and cramping in the legs at night is another common feature, often experienced by those who usually sleep flat on their back. A pillow under the knees may help but those affected commonly report that they have had to resort to sleeping curled up on their side.

Sometimes the narrowing will be confined to the outer edges of the spinal canal, called the lateral recess, or the opening between the vertebrae for the nerves called the neural foramina. If so, specific nerve roots tend to be affected, causing leg pain where the nerve goes to in the leg (sciatica) and sometimes other features such as altered sensation and pins and needles.

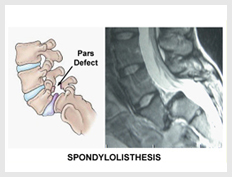

These two conditions are related and are quite common, being present in about one in twenty people. Fortunately the problem usually causes no more than occasional mild back ache and most people never know that the abnormality is present. It may be picked up as a coincidental finding on x-rays.

The separation of the back part of the vertebra means that the vertebral body is not properly restrained. The disc becomes over-stressed and wear and tear changes can start to develop. The vertebra can start to slip forwards a little. This is called a spondylolisthesis. In addition to causing problems of back pain

Introduction

An accurate diagnosis is always important in managing any clinical problem. When treating problems in the lumbar spine, clear and detailed information is an absolutely key factor in success. With different structures and different levels of the spine being affected to varying degrees by a range of degenerative processes, getting this wrong can have serious consequences. With reliable and complete diagnostic information, an appropriate surgical strategy can be tailored to the specific problems affecting an individual’s lower back. The wear and tear processes that can occur certainly do not always cause problems and a key question to be answered is: where is the pain coming from? This is one of the most important questions we will attempt to answer, using the most up-to-date and detailed spinal imaging techniques.

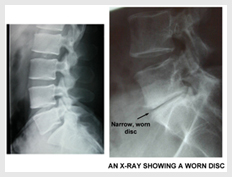

X-rays have been used for almost a century and are still the first line investigation of the lower back. Standard front and side views provide a great deal of information about the bony anatomy of the spine and a wide range of conditions which affect the bones, facet joints and intervertebral discs. Degenerative changes cause well recognised features. The intervertebral discs themselves cannot be seen but much can be learned about the condition of the discs from what is termed the ‘disc space’ (the gap on x-rays between the vertebrae occupied by the disc) and the bony features around this.

It is no exaggeration to say that MRI has revolutionised our management of conditions affecting the spine and it is really impossible to do justice, in a few short paragraphs, to this truly amazing form of imaging. MRI provides highly detailed pictures of the spine, including vitally important information about structures such as the intervertebral discs, the spinal cord and nerves in the spine.

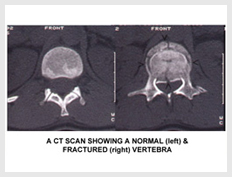

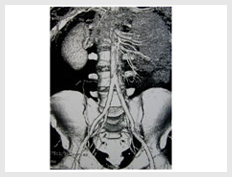

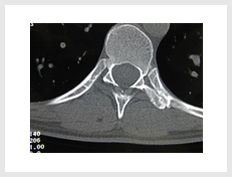

Whereas an x-ray effectively provides a two dimensional ‘shadow’ of the spine, perhaps with views from the front or from the side, CT scanning uses views taken from every angle around the spine, either in a full circle or in a helix. Sophisticated computer hardware and software can then analyse and reassemble the radiographic information to provide sectional slices in any plane through the body. The equipment can even reconstruct three dimensional views of the spine from any angle.